(12.12.1959–16.11.2015)

Although happy to see the first edition of our online journal, our mood is, however, darkened by a tragic event, passing away of Ivan Yurievich Chernov, a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Professor, Head of Department of Soil Biology, the Faculty of Soil Studies, Moscow State University, member of the editorial board of our journal.

The son of outstanding Russian ecologists Yuri and Nina Chernovs, Ivan was a rare specialist studying yeast in nature. He was the founder of new research field – studies of biocoenotic complexes of microorganisms.

His scientific legacy is is especially valuable because he studied the issues of microbiology on the basis of general biology and ecology concepts. These include the manifestations of natural zonation of microorganisms, the succession of their groupings, and cenotic strategies of species, the identification of new specific communities, the fractal character of their distribution in nature, and the problem of species among microorganisms. Acknowledging the need to use molecular and genetic methods, I.Yu. Chernov urged to employ the general biology approach when dealing with the problem of species among microorganisms. The analysis of huge amount of material, gathered in the ecosystems of different natural zones, allowed him to state that the identification of new yeast species must be conducted from the point of view of ecology.

Ivan Chernov had profound knowledge of general biology and, as a scientist, he was deeply concerned about the inadequate solutions of ecological problems in the human-nature contact. All this explained the help and support that he provided during the setting up of our journal.

The journal editorial board expresses sincere condolences to the family, friends and colleagues of Ivan YurievichChernov.

MEMORIES OF IVAN CHERNOV.

“HOW IT ALL BEGAN…”

(These are the exact words that Ivan told me when giving me his the abstract of his doctorate thesis (N.Matveeva)).

***

In 1965–1977 there was a biogeocenosis observation station near a fisherman settlement Tareya in Western Taymyr region, in the middle of the Pyasina River. The station was founded by Boris Tikhomirov, who I had worked with in the laboratory of the Institute of Botany at the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1969, after graduating from the Biology and Soil Studies Faculty of the Leningrad University. In summer of 1965, Boris Tikhomirov and the five of us, botanists working with him, went to Tareya observation station. But his plans were to make the observation station a complex one, so in the following 1966 year, already 16 different scientists gathered there, among them was Yury Chernov, whom Boris Tikhomirov knew from some meetings in Moscow academic circles. He used to tell us, ‘There is a certain zoologist, Yura Chernov, he will come with his guys (students)’. And duly he arrived, with three students … all girls.

And thus began my acquaintance with Yury Chernov. The ‘Tareya’ station (as we would call it) in its most prolific years was the centre of magnetism for a great number of different biologists from various institutes across the country. One summer (the season of field works began in June, sometimes in May, and finished in September) there were up to 40 people at the station, with large numbers of university and post-university students. The majority of people at the station were quite young. The most adult were Boris Tikhomirov and Vera Aleksandrova, who at the time were already established renowned scientists in the studies of tundra. In 1969, as we celebrated the 60th birthday of Boris Tikhomirov, all biologists working in Western Taymyr region during that summer, came by hydroplanes and motorboats, as well as practically all zoologists from the Research Institute of Agriculture in the Far North (Norilsk). The atmosphere reigning at the observation station was both serious, as suitable for scientists, and reckless, according to the age of the majority of participants. They also established great relationships with the local fishermen, who were ex-convicts serving the sentence for various offences. All in all, the bright patchwork of characters. We had lots of talks and argued a lot as well. The initiator of discussions, or to be exact, their agent provocateur (although in the best sense of this word) was Yury, who argued with Boris Tikhomirov and was invariably polite with Vera Aleksandrova.

At the time he was already obsessed with the research idea of natural zonation and gradually developed the main concepts for it for the Far North region. I remember how he, during our 22-delay in the airport Ust-Tareya in September 1967, while waiting for the weather conditions to improve, he carefully probed, whether it would be an absolute boldness on his side (at the moment the future academician was only 33) to write a book on natural zonation. (The book ‘Natural Zonation and Land Fauna’ came out in 1975). The last time I went to the observation station was in 1970, Yury was in 1971. Gradually, his ideas on natural zonation gained popularity. The following year, together with my friend and colleague Taimi Piyn, Estonian lichenologist, we went to the Arctic tundra sub-zone, to consinue the development of Chernov’s ideas. As Tareya was the classic representation of the middle part of the tundra zone – the sub-zone of typical tundra, we went to the East Taymyr region, to the Maria Pronchishcheva Bay, and there we stayed at the base station. Yury spent that field research season both in observation stations in Kazakhstan and on the Yenisei River. On the latter, he took his son Vanya with him. Vanya already has the exedition experience – he was to Abkhazia with his mother. I heard about Vanya, naturally, since 1966. I saw him during my visits to Moscow while preparing report on research in Tareya, and Yury brought him a couple of times to Leningrad as well.

Our experimental studies in Western Taymyr region had success, and the following summer of 1973, we went to Maria Pronchishcheva Bay already as a group of five: I was the head of the group, Yury with his son Vanya, microbiologist Olga Parinkina, and a recent graduate, geo-botanist Olga Sumina, Taimi was to join us later. Vanya, according to calculations, was 13 that summer. I think it was this year that his parents decided that he would skip one year at school and go from the sixth form straight to the eighth. The reason was that studying came easy for him and his aptitute for misbehaviour was flourishing (as his father said much later, ‘Such a pain in the back he was’). And so, Vanya was going to the field trip with us burdened by drilling the school subjects, to top it up he had to read some Russian classics as well.

The North showed him, and not only him, but us, the experienced ones as well, what it really was. On the 20th of June, Olga and I flew to Moscow, where Yury with Vanya (Olga Parinkina was to get to the station later) joined us. The flight was delayed. Not surprisingly. We spent the evening and the night at the airport. The crowds were huge, people slept on window sills, taking turns. Next day we managed to get to Norilsk. We landed in Alykel (Norilsk airport, in those days not as tiny and old as it was in the 60s, but still far from what it looks like today). But we had to go further to Khatanga, in the east of the peninsula. Again, no flights, we were stranded for indefinite time and had no opportunity to get to Norilsk. The place crowded, no place to sit down, everybody angry. We and our numerous packs managed to camp top-class – in the luggage-storage room near the toilet. We took naps in turns and even slept soundly on the packs. All through the next day we heard the same phrase that the flight was being delayed. So we set up an activist group who pested the airport manager, but their activities yielded no results. It was the third day practically without sleep for us. In the evening, Yury voiced his decision – we all go to Norilsk, to the hotel, sleep and in the morning come back. The plan did not guarantee that during our absence the plane would not go without us. 23rd of June – and the situation stayed the same: no flights, not even in prospect. And then, suddenly, a charter flight appeared out of nowhere on LI-2. They could take only luggage and three people. So the three of us took the flight (I, Olya and Vanya), and Yury stayed in Alykel for one more sleepless night. Yet, one more problem was awaiting us – Vanya was underage and so without a passport. Khatanga is a borderline territory, special permits are obligatory. Vanya was registered in Yury’s permit, but Yury stayed behind. So, we were looking forward to spending the night at the borderguards station, anyway it would be warm there and we could actually lie full length on the benches at the station. But everything went smoothly. The North does not have that maddening beaurocracy. They checked us, believed what we said and allowed us to stay in the inn. Yury and Olga came by night the following day. All in all, it took us four days to get to Khatanga. Only on the 27th of June (and that already amounted to a week), having left Yury and Olga’s passports at the inn in Khatanga, we flew to Kosisty – the airport on cape Kosisty in Yakutiya, from which we were to fly to Maria Pronchishcheva Bay. Another 9 days had to be spent in Kosisty because: a) the helicopter broke down, b) the weather conditions were bad, c) no helicopter from Khatanga. This waiting is not for weak-hearted. All the twists and turns of our journey were recorded in the diary, which we started to write there, in Kosisty. It is here that life taught both Ivan and all of us a lesson how one can (and must) use the circumstances (or withstand them). Taking his old portable typing machine (oh, where are you, netbooks of the future?), using the stove as a desk, Yury (in winter coat and hat, the room temperature was far from hot) was typing the chapters of his future book. That was ‘Living Tundra’. It was released in 1980 and translated into English in 1985. Its second revision was to be done by his followers, according to Yury’s wish. So, Yury was writing and we had the nerve to criticize that as soon as we read.

Finally, 7th of July and we flew to Maria Pronchishcheva Bay by MI-4 helicopter. In total, 18 full days passed from the 20th of June. Neither before that, nor afterwards, had it taken me so long to get to the field research spot. Vanya seemed not to mind. No whining, no boredom. There was always some occupation for him. The flight lasted 2 days. The base station struck us with its comfort: a big warm house with a kitchen, dining room, sitting room (also an extensive library), cinema, bedrooms and (!!!) Russian sauna. Common exultation and settling down with household matters and the research lab (we had a zoologist and a microbiologist in the team). And the Russian sauna! This all happened during the 8th of July.

The following day was the first of day of our adventure in the most beautiful and exciting place in Taymyr Peninsula, which I had already had a chance to feel a year ago. Apart from me, only Yury had seen the Arctic tundra, not in Taymyr, but in Vaigach and Anabar. The results of our work were published 5 years later (in 1979) in the book ‘Arctic Tundra and Polar Deserts of Taymyr Peninsula’. How did our life seem for a 13-year-old boy? Following are some diary entries made by Vanya.

10.08. After breakfast we went to select the work sections (how to work on them to be asked from Yury and Olga). Yury, Olga and Nadezhda argued a lot while choosing the sections. They shouted, insisted, on an on for about half an hour. Finally, stuck several boards in the ground and went home. During all this, I was running around with the camera (the lenses of unknown make), hunting for birds. So, I spent my time much more interestingly than Yury, Olga and Nadezhda. After lunch, not giving us even time to rest, Nadezhda dragged us again (me, Yury and Olga) out into the tundra, again to mark the sections with boards (and I again was running around with my camera). When we got back and had some food, we were informed (the bosses informed us) that that day was a working Sunday and big cleaning day (it was anyway a normal week day) and sent us outside to pick up litter and pile it in specially designated places. And there were specially designated mechanical means for that! So, our mechanic guy, Vitya, aimed at blowing all the rubbish away with the water from the pump. The plan failed. The reasons:

- The hose burst.

- The hose burst again.

- The hose tip went off and the water was over Yury.

During all these procedures we quickly cleared the rubbish and even made a stoned path from the house to the rubbish pile. And went home to sleep.

Note: And there was no promised cinema. Ivan.

As seen in the diary that enumerated countless problems of each of the participants, Vanya’s major problem was how to join the research work and how to talk his father into letting him go hunting.

He joined the research work all right – he was digging the soil trenches and helped to gather samples (that was the first experience for the future student of soil studies), taking images of birds, digging worms (the field trip was a multi-science one), conducting weather studies, making paper bags for different samples, measuring the depth of thaw penetration in the eternal frost layer (his record in the diary: …so, I got up, had some food and went out into the tundra to help Nadezhda.(I am a labourer, though!) I was to help with that: I had to take a small piece of wire in one hand (about 1-1.5 cm thick and 1 m length), with one end of the wire sharpened and the other turned into a coil, on the surface of which there are tiny, hardly noticeable incisions after each 5 cm. Then I had to stick that piece of wire into the ground, get it out, stick it again and get it out again, stick out, get out, on and on again. This sticking in and getting out had to be repeated 100 (!) times. After that, the piece of wire had to be dipped in the puddle (the water there is so-o cold), and all of this is called “studying the conditions of organisms development in tundra zone”).

But he did manage to go hunting (His father was a passionate hunter and Vanya inherited this).

Here is what he wrote about it. I went with them (on the condition that we would boil some tea and fatherwill let me go fowl hunting. And I did! I shot! Waders! Five times! All missed! But father found some new wader (tomorrow hunting it). Says it’s sensational (new wader species in the North).Another of Vanya’s records:After dinner I went to do what Nadezhda told me, to fetch a glaucous gull.So, I am walking and then, right into me (swear to God, that’s the truth) flies a massively huge glaucous gull. I take aim and then baaang!.. missed. I take aim again and baaang! … missed again. Nothing I could do. I went home to sleep.

Evenings Vanya used to show films – he learned how to operate the film projector in perfection, and was extremely proud of it. We talked a lot, and Vanya listened to and then commented on the science discussions which accompanied his life there. One of the strongest impressions of that summer was the walruses. They came (on the 4th of August) to the long spit, in summers there was a permanent walrus rookery there. The rookery was about 1.5 hours walk from us. The weather was disgusting – clouds, cold, drizzle, and strong wind. Olga’s notes in the diary: We walked the spit very slowly, afraid to frighten the animals.We started taking photos from a long distance away. We started to approach them – 100m, 50m, 25m, 15m.. We all were feverishly photographing the walruses, themselves with walruses in the background. Closer – 10m, 8m, 6m.. Some animals went into the water – huge in size, some brownish-greenish, as if overgrown with moss, others dark, with huge tusks, old walruses scarred. The interest of walruses towards us is no less than ours towards them. Even those that went into the water come back slowly and watch us. The animals had different characters and temperaments. Some even did not move, others were scratching phlegmatically, sneezed, while turning from side to side.

Yes, it was fun. The next time I chanced to see walruses was in the European North – on the island Golets in the Barents Sea, 33 years later. For others from the expedition in Maria Pronchishcheva Bay these walruses were the only ones in their lives.

Between science, hunting, cinema, and household chores Vanya was reading fiction (it was good that the library had lots of books of Russian classics) and perused the textbooks: We started packing.When the packing started, I was quietly lying and reading chemistry book. I racked my brains over calculating the heat of uranium-235 decay into barium-56 and krypton-36

(92U235+0n1 = 56Ba143+36Kr92+30n1).

The light of understanding was already glimmering, when suddenly the cry

‘Vanya! Get me two boards!! I ran and sawed the two boards.

Vanya!!! Quick, pack the gunshells! I promptly did.

Vanya!!! Do not disturb me!!!

I did not to disturb anybody, so I took the double-barrel gun and went out. And here I got terribly unlucky. First I shot the glaucous gull, it said ‘Quack-quack’ and landed on the water. I ran up to it, it fled into the sea. Then I shot the duck. It also said ‘Quack-quack’ and also landed on the water. So they both escaped me!!

On the 7th of August the ‘board’ came (helicopters are traditionally called ‘boards’ in the North) with Taimi. Leaving Olga at the polar base station (she managed to leave the bay only on the 15th of August, not with the helicopter but with the survey vessel), five of use flew to cape Kosisty. Taimi and me first stayed at the geologists’ camp at the foot of Tulai-Kiryaka uplands, there were stayed till the 16th of August and then, after a short stop-over in Kosisty we got to the island Bolshoy Begichev with the same survey vessel that brought Taimi. There we worked till the beginning of September. Yury, Ivan and Olga got straight to the airport, where they were waiting for the transport to get them further. (Yury was burning the stove and typing his book, not forgetting to follow the carter flight into the bay to fetch Olga Parinkina. Olga Sumina studied her French textbook, Vanya was playing ping-pong, snooker, went to the cinema, drew the coats of arms of the places we had visited) This lasted till the 10th of August.

Maria Pronchishcheva Bay, Norilsk, Khatanga, Кosisty coats of arms

Maria Pronchishcheva Bay, Norilsk, Khatanga, Кosisty coats of arms

We flew by AN-2 (“Annushka”). In Khatanga we stayed till the 12th and then flew to Norilsk and from there straight to Moscow. This was the first trip for Ivan Chernov into the Arctic. It was his baptism of fire and he passed it.

After it, his participation in the expedition of the following 1974 year, into the zone of polar deserts, was unquestioned. Our point of destination this time was Cape Chelyuskin, the northernmost point not only in Eurasia, but of the whole continent, at 7743’ N. Same as in the previous year, we first had to reach Khatanga. And from Khatanga we were to take a helicopter flight (the runway was not fit for airplanes in the season from end of June till the beginning of July) to Cape Chelyuskin. (It is impossible to imagine the possibility of such an expedition for the Academy of Sciences in these days, considering the costs of a helicopter hour we have now). That time there were seven of us. The four participants of the last-year Odyssey (I, Yury, Vanya, Olga) were joined by the zoologist Bella Striganova (Yury’s co-worker in The laboratory of the Institute of Problems of Ecology and Evolution in Moscow), geobotanist Viktor Mazing (professor at the University of Tartu, Estonia) and the microbiology student Marina Chugunova from Leningrad. We reached Khatanga the same day we flew from Moscow. Compared with the last year journey, it was sheer luck. The first and the last time, as it turned out. There was no fuel for our expedition in Khatanga (for MI-8 helicopter), though during previous flights, the payment always covered the fuel as well. A week was spent in search of fuel, fuel barrels, bushings, etc. Then the geodesists agreed to take us into their field camp at the Shrenk river (“… it’s a stone’s throw to Cape Chelyuskin from there… you’ll manage.. somehow”). Then the weather turned bad – first at our place, then on the road. Finally, after a week, with some adventures, we managed to get to the middle of the Shrenk river at 73º N, which was a heaven’s gift for both Chernovs, both father and son. Science is science. But what awesome fishing was here! Huge salmonids! Vanya set the fishing rods in the night (later he described the nights as sunny in one of his school essays, causing envy and approval of his literature teacher). He would check them regularly and bring back metre-length fish which they then cleaned together with his father, and Yury salted them, following some special “salmon” recipe.

This salted fish later had astounding success at Cape Chelyuskin. Five happy days passed in a flash. The tundra was magnificent: typical varied landscape, wild deer. Everybody was running around enthusiastically – along the valleys, water divides – took photos (three of the team found themselves in that paradise named the Artctic for the first time), swam across the rivers, and I already mentioned the fish. On the 18th of July the helicopter arrived to the geodesists, we talked the pilots ‘to give us a lift’ till the required place and signed the payment papers. The flight was long, with several landings. The thick fog above the shore threatened to make us go back to the station, but the pilots in the North are ace flyers, by night we had already been at Cape Chelyuskin.

We carried the luggage on a drag sledge from the helicopter to the settlement

We carried the luggage on a drag sledge from the helicopter to the settlement

The settlement had excellent organization. It had an airport and the polar base station, a number of heated houses, where we were provided housing and place for the lab. There was also a dining room (one worry less), sitting room, snooker, cinema, and the Russian sauna, of course. Polar deserts are a stone’s throw away – just across the runway. There, following the same algorithm we used in previous field works, the sections were chosen for complex studies by botanists, zoologists, and microbiologists. Vanya was my constatnt companion at that time, as all botanical studies and procedures were my sole responsibility. All technical aspeces, such as drawing the ropes to mark the sections 10×10 m, ‘cutting’ into 1 m2 areas, digging soil trenches, taking soil samples, – all of these were Vanya’s tasks. Yet, he was already an experience field researcher, so he did more qualified jobs as well, such as drawing the horizontal structure of communities, which in the polar deserts was just phenomenally varied.

Yury takes samples, and Ivan, standing on the box, takes photos of the structure.

Yury takes samples, and Ivan, standing on the box, takes photos of the structure.

What a job it was for Vanya, especially when the time came to take cutttings so as to determine the biomass productivity. Considering that the vertical profiling was practically absent, the vegetation was plastered to the ground, the sampling had to be done not even on the knees, like in the tundra, but lying on the stomach. As the scientist loved to joke, this was the job for students and convicts, and that time we exploited the ‘child’.

And all this happened when the temperature outside did not exceed 1–2 ºC (the standard answer to the question ‘What’s the temperature today?’ was ‘plus zero’), and was accompanied by 100 % humidity and constant forgs, sometimes snow or rain. There was neither fishing nor hunting. But Vanya was not bored. He went out to the polar deserts with us, and if his caring father (overbearing, in Vanya’s idea) made him stay at home, he found some typical for boys ccupation – cast lead bullets (once he even cast several crosses with Christ), drew bottle labels for our evening-time drinks (as the whole days were spent in the cold outside), which were spirits infused with lemon peels or mixed with juices, including tomato juce, so we got famour ‘Bloody Mary’ (and here the salted fish came useful). The boy played snooker with maddened by the lack of activity (the weather did not permit flights) helicopter pilots, and in the evenings showed films as a professional cinema mechanic. He also had to read Russian classics, such as ‘Cherry Orchard’, the experience that he described in the diary as absolutly disgusting. But there was no arguing with his dad.

A small room (about 15 m2) in the hostel for airport employees was given to us and served as a laboratory (it also served well as a place to sleep for the men, the woment slept in the settlement). The microbiologists quickly occupied practically the whole place at two excellent lab tables near the window (those were constructed from wet dirty wood by Yury), piling it with Petri dishes, test tubes, microscope, burners, etc. Bella found place somewhere in the corner with her binocular microscope. The Estonian professor worked on a tiny table that was erected in the middle of the room. The geobotanist (also the team leader) with his herbarium and sample cuttings had no space left for him, naturally. The airfield management took pity and allowed us to use the old sauna house, which became the place for first lab analysis and where the funnels for soil invertebrates exctraction were placed. (Yury was busy with it). The accompanying atmosphere of microbiology, equipment, and near-sterility appealed to Vanya greatly. As he would say later, ‘It was such Science… compared with herbariums and cuttings…’.

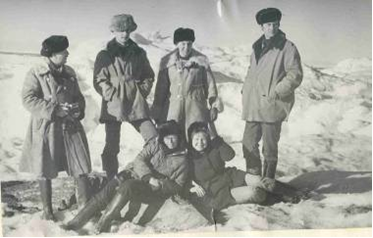

One notable day, on the 30th of July, the first snow started to fall in the morning, then the fog settled, and then the strong wind began to blow. In a short interval, when the sun was shining, we rushed to that northernmost point of the continent to make photos. All the participants of the expedition have these rare photos. They are standing near the crag behind which is the Arctic Ocean covered in ice.

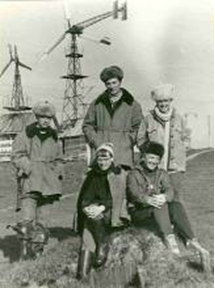

At the northernmost point of Eurasia (standing: Viktor Mazing, Vanya, Bella Striganova,

At the northernmost point of Eurasia (standing: Viktor Mazing, Vanya, Bella Striganova,

YuryChernov; sitting: Nadezhda Matveeva and Marina Chugunova).

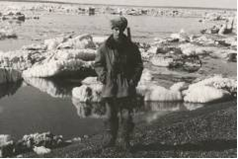

This is Vanya’s photo:

The following entry from Vanya’s diary, which he was writing alongside the adult researchers, joining in the ironic style, shows how he looked at what was going around him:

3.08. The morning was typical. Still sleeping, I heard father’s voice, repeating tediously, ‘Vanya! Hey, Vanya! Vanya!! Ivan!! Wake up! Do you hear me!? Vanya! Vanya! Vanya! Get up!! and on and on. There was another quiet voice in the background, thinner, speaking even more tediously, ‘You see, Yury, from the point of view of geobotanics, phytocenosis (or phytosynosis, have no idea) of the tundra zone, has its own characteristics, while bio-geocenosis of evolutionary succession…’. This words, it seemed, were addressed to fatether, but without turning his head to it, he just growled and started waking me up even more vigorously.

Time before lunch went like in a haze: somebody went to tundra, somebody was arguing on bio-geo, I was heating the stove in the sauna. After lunch everybody went to the sauna, to wash away the week’s dirt in a steam-bath… After supper we watched the film ‘Pechki-lavochki’. Viktor decided to watch it, but went away at once, hearing the drinking song and seeing the drunk men. He shouldn’t have! There was festive drinking with some food; people were drinking ‘Bloody Mary’, which went so smooth and soft (perhaps hence the name). But they finished quickly and I went to bed with a gnawing feeling that tommorrow morning they will again start waking me up. Vanya.

The bad weather was beginning to oppress the older participants of the team, who started to have some urgent business in far away places. That is why, as soon as the unexpected helicopter arrived (9th of August), Bella and Viktor flew to Dikson, and from there practically at once straight to ‘the mainland’. Yury was also beginning to get nervous. Although the conditions were quite tolerable for work, but he disliked the idea that Vanya can be late for the beginning of the school year (the object of dreams for Vanya, and we planned and try to organize one more trip to the Shrenk river). The weather slowly setttled, the night frosts dried the runway and, on the way to some islands, not only the helicopters (MI-8) but planes (LI-2) started to appear. So, in the evening of the 15th of August, to Vanya’s utter disappointment, after the turmoil of weather and yes/no appearance of the helicopter, Olga, Yury and Ivan flew to Dikson with the helicopter. Marina and I were left alone. Yury’s intuition did not fail him (as usual). After they left, the weather did not permit flights till September, and we waited till the ordered flight from the 19th of August till the 4th of September. When, after several urgent messages to the management of civil aviation in Krasnoyarsk and Moscow, AN-2 plane arrived, and we flew to Khatanga. And then, on the 6th of August, we flew to Moscow and home to Leningrad.

The next summer, aiming to finish the zone profiling, we planned to work in southern tundra. We chose a good place to the south from Tareya on the Pyasina River, in the mouth of its subsidary – the Dudypta river. A station was based there, not the polar one, just meteo-survey, ‘Kresty’.

And there we stayed, sleeping on the floors.

And there we stayed, sleeping on the floors.

We worked there three seasons – from 1975 to 1977. Ivan was with us only during the first year, which was so full of events that it would take ages to describe them all.

He was already an independent, and quite a successful huntsman. On one of our joint trips, he shot down several ducks, which we promptly cooked on the fire, thank God there is no shortage of fire-wood in southern tundra – branches of tall willow trees. We were happy and proud afterwards. A hare was also among his hunting trophies. But all this happened alongside the work at the sections, in passing through vast bogs to the rocky peaks, getting across the river. We often made these trips together, to save him from excessive attention or educational measures of his father.

Yury also spent one full field season at ‘Kresty’ station only in the summer of 1975. He spent the next summer (that year he got his higher doctorate degree, with the thesis ‘Animal World of Subarctic and Environment Zonal Factors’) in the southern seas, on the ‘Kalisto’ ship. In 1977 he made a short visit to ‘Kresty’ in August, after his journey to Djanybek.

In this period Ivan finished school and went to study to Moscow University, to the faculty of Soil Studies. As he later told me, and the students, he did it to continue his trips to the North, and not for the sake of some science, but just to go fishing and hunting. Maybe this is what he really was thinking at that time, but his family background and traditions that included expeditions, the example that his parents set for him, undoubtedly played their role, and the choice was made in favour of biology. And the fact that from all the spheres of biology he chose exactly microbiology, and soil biology, was the result of his perception of the work of microbiologists at Cape Chelyuskin. And maybe he ded not want to take the same path his parents had chosen. Their opinion was undoubtedly strong, but a little bit too strong, he wanted something of his own.

The next time Ivan travelled to the North already a university student. This time he went to the area near Dikson village, in the subzone of Arctic tundra, the same as in his first trip to the North, but this time it was in the west of Taymyr Peninsula. We worked in that area three seasons (1978–1980), between the set snow periods. We lived in four wagons that the Botanical Institute bought for us from geologists. The wagons, for sake of their safety, were moved to the village for winter,

and in spring they were pulled across the snow (or its remnants, but the ground was still frozen) by tractors to the field camp location – at a small peninsula 2 km to the south of the village.

In September they were moved back to the village again.

Ivan was always zealous in those activities.

Ivan was always zealous in those activities.

In different years, the number of researchers in the team was varied, between 9 and 7 people. The invariable (since the trips to Cape Chelyuskin and life at ‘Kresty’ station) group, consisting of Yury and Ivan, Bella Striganova, Olga Parinkina, Lida Zanokha and me, at different periods was joined by lichenologist Taimi Piyn and bryologist Leti Kannukene from Estonia, entomologist Vladimir Lantsov, zoo Anna Tikhomirova.

At the camp: Yury Chernov and Bella Striganova

Lunch time (hot summer of 1978)

Lunch time (hot summer of 1978)

All the works were typical, and were performed following an established route – choosing the permanent areas so as to be able to compare the results from different zonal areas of the Taymyr Peninsula. One more object of research was added – the yeast fungus (as Ivan later termed them in his thesis in 1984). And before thesis there were other papers and graduation diploma – all based on the material that Ivan gathered in Arctic tundra. His post-graduate research was on typical tundra (Taymyr region). Ivan worked hard, but this did not prevent him, with due regularity (sometimes sweeping all the Petri dishes from the table), to grab his rifle and go hunting wild deer (we always took care to have a license). In his love for hunting, his father was his equal. And how can one forget how Ivan once chased the geese on the Sibiryakov island (Yenisei Gulf), when in he threw off his boots, running full speed from excitement, and he did catch the goose!

Hunting and fishing were just fantastic at the small river Lenivaya (near the river Pyasina), where the four of us flew in August 1980, leaving our colleagues suffer from cold at Dikson (the summer that year was just horrible, locals said there was no summer at all). We were, though, planning to get to the Shrenk river, which was the object of desire for Ivan. But the small helicopter MI-4 could not carry enough fuel for both the outward and inward flights (usually the whole amount of fuel is carried onboard, as there was no possibility to get it there).

And here the father and son enjoyed their fishing to their hearts’ content. The work was not just at one observation station. We explored the routes, the foothills of the Byrranga Mountains. The food was abundant, we took care of that. But what is life without some good fish! There were lots of it, but only the Arctic grayling, though.

Cleaning and

drying the Artic grayling.

Ivan often went hunting along. Sometimes he joined either me or Lida in longer journeys.

Life in those days, including the organization of expeditions, was simple. No walkie-talkies. In the airport at Dikson we arranged the time and day when they would come to get us back. Our friends, geologists from Krasnoyarsk, also backed us up – when going down the nearby river, they stayed with us for a couple of days. The day they arrived, Yury and Ivan procured a deer for dinner. The geologists did not come empty-handed. They brought a goose. In the end, they went by the river to the polar base station at Cape Sterlegov, and then reminded the people at the airport in Dikson about us. In those conditions you have to be ready for everything. We packed our things and equipment in time, but the big tent was put on till the helicopter landed.

Still no sign of a helicopter (Yury found a place to have a nap)

Still no sign of a helicopter (Yury found a place to have a nap)

The helicopter pilots are usually very responsible. The craft arrived on the agreed date.

Years later, during another helicopter flight (also in Western Taymyr Peninsula, to the south from Dikson), Ivan and Yury learned (from our colleagues, who arrrived later), that the former became a father and the latter a grandfather – Danila Chernov was born in July 1982.

Standing: Yury and Ivan. Sitting: Lida Zanokha, Nadya Sekretareva and NadyaMatveeva.

Ivan wrote and defended his thesis ‘The Ecology of Yeast Fungus in Taymyr Tundra’ in 1984, where he showed taxonomy, spatial distribution (in substrates and soil profiles), and the possibility of plant substrates decomposition, seasonal dynamics, the structure of yeast poopulation. He turned out to be the most assiduous pupil among all of us. Having research trips to the North as a boy, he applied all the approaches in his field, that were used for studying absolutely various groups of organisms. This, it seems, had never been done before. Not for the studies of the North, that’s for sure.

After 1983 Ivan had no more Arctic journeys. But the experience that he got of (as my foreign colleague put it) ‘obsessed with zonation’ and working in different sub-zones in the Far North was invaluable. He later transferred this experience and research excitement to other biomes – from forests to deserts (from Central Asia till Israel). The result of that was his higher doctorate theses ‘Synecology and Geography of Soil Yeast’ in 2000.

***

In summer 2016 we were planning to go to Dikson to see how the yeast was going after 36 years.

***

These words are precious for me, that Vanya (already Ivan at that time),

wrote to me when giving me the book ‘Yeasts in Nature’:

…Nothing of this would be possible without you and my father.

NadezhdaMatveeva,

Doctor of Biology,

leading researcher at the

plant laboratory of

The Far North at the Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Key Publications List

- Babieva I.P. Yeast in Tundra Soils of Taymyr Region/ I.P. Babieva, I.Yu. Chernov. Soil Studies. No. 10, p. 60–64.

- Chernov I.Yu. New Yeast Species of the Genus Cryptococcus in the Tundra Soils/I.Yu. Chernov, I.P. Babieva. Microbiology. 1988. Vol. 57, No. 6. pp. 1031–1034.

- Chernov I.Yu. The Geography of Microorganisms and the Structure of Ecosystems/ I.Yu. Chernov. Proceedings of the USSSR Academy of Sciences. Geography Series. 1993. Vol. 6, pp. 49–58.

- Yu. Synecology of Yeast Fungus in Subtropical Deserts/ I.Yu. Chernov,

I.Pl Banbieva, I.S. Reshetova. Advances of Modern Biology. 1997. Vol. 117, No. 5. pp. 584–602. - Chernov I.Yu. Microbe Diversity: New Possibilities of the Old Method/ I.Yu. Chernov. Microbiology. 1997. Vol. 66. No. 1. pp. 91–96.

- Maskimova I.A. Structure of Yeast Fungus Community in Forest Bio-Geocenosis/ I.A. Maksimova, I.Yu. Chernov. Microbiology. 2004. Vol. 73. No. 4. pp. 558–566.

- Chernov I.Yu. Latitude and Zonal, Space and Succession Trends in Yeast Fungus Distribution/ I.Yu. Chernov. Journal of General Biology. 2005. Vol. 66. No. 2. pp. 123–135.

- Glushakova A.M. Seasonal Dynamics of Community Structure of Epigenous Yeast/ A.M. Glushakova, I.Yu. Chernov. Microbiology. 2010. Vol. 79, No. 6, pp. 832–842.

- Chernov I.Yu. Annotated Listing of Yeast Species in the Moscow Region. I.Yu. Chernov,

M. Glushakova, A.V. Kachalkin. Micology and Phytopathology. 2013. Vol. 47, No.2, pp. 103-115. - Glushakova A.M. The Influence of Invasive Species of Grass Species on the Structure of Soil Yeast Complexes of Mixed Forests, as exemplified by Impatiens parviflora DC/ A.M. Glushakova,

V. Kachalkin, I.Yu. Chernov. Microbiology. 2015. Vol. 84, No. 5. pp. 606-611.